The Not-Terribly-Astute Observation

I frequently marvel at the grand 401k experiment that we’re embarking on. In the absence of pension funds, all of us with 401k’s are pension fund managers. As such, our future livelihoods depends on:

- Having the discipline to save early and often by forgoing consumption now

- Understanding how to leverage the US tax code to our benefit

- Understanding an appropriate asset allocation

- Understanding the power of compound interest

- Understanding the debilitating effect of compound fees

- Understanding the history of financial markets

- Understanding of short-term vs long-term risks

- The ability to tolerate occasional market corrections of 50% or more (this one is easier said than done)

- Understanding the debilitating effects of inflation over time

From my perspective, the grand 401k experiment is failing most of us. It’s my experience that the vast majority of people have zero training on the above. The only university students who would actually have received some of this training is perhaps a subset of finance students. Recalling my time as a college student in engineering, I often didn’t want to learn what was being taught and the rate of absorption was pretty low. Consequently, I’m not even sure finance students are adequately prepared to face the real world in appropriately handling the above. Consistent with this assertion, I’m aware of no finance class which adequately covers the intricacies of the U.S. tax code that would position a student to succeed on this dimension.

So those are my not-terribly-insightful thoughts on the state of affairs right now. We’re collectively — knowingly or unknowingly — trudging through life as pension fund managers. Most of us are vaguely hoping there will be enough money to retire in several decades. Other of us have come to the stark realization that there is certainly not going to be enough. The cruelty of this realization is that it happens decades too late. The gravy train of magical compound interest departed decades ago.

However, not all is lost, even for those to have missed the gravy train of decades of compound interest. They say best time to plant a tree is decades ago, but the second best time to plant a tree is today. Similarly, the best time to start saving is early in one’s life, but the second-best time to do so is today.

What I Hope to Have Accomplished on this Blog

Part of the motivation for this blog was to do the unthinkable — to spill the beans about money and how it actually works; something that most people keep a closely guarded (and oftentimes embarrassing) secret. I’m an employee at a public institution, meaning that my salary is readily googleable for anyone with an internet connection, my name, and about two minutes of effort. Perhaps it’s this salary transparency which initially helped motivate me to spill the rest of my beans — or perhaps it was a moment of insanity — I’m unsure which.

What I hope I’ve accomplished so far with the blog is to convey the obvious:

- It’s important to remember that one’s investing horizon is (hopefully) many decades long. If someone is in their 20s, they ought to be planning for a seven (or eight or nine) decade long investment horizon. This is an unbelievable amount of time for compound interest to do it’s magic (but also an unbelievable amount of time for inflation/investing fees/tax drag to do wreak havoc).

- Even if my life is tragically cut short by the “proverbial bus”, my wife and kids get my money so the appropriate investing horizon is still many decades long.

- If you are frugal today, thanks to the magic of compound interest, you’ll be substantially richer in the future.

- The way to generate these elusive investable dollars is to spend less than you earn. It’s obviously easier to do so while keeping lifestyle inflation in check and trying to grow your earnings.

- This frugality challenge isn’t metaphorical. If you desire to be wealthier, you must save more today. To do so, you must spend less today. Actually brown bag it to work. Actually call up Verizon/Xfinity to cancel your $200/mo TV/Phone plans. Actually drive a hooptie (my car of choice is a 2010 corolla bought used for $9k with 45k miles on it from mormon missionaries many years ago). Actually use the library in lieu of buying books/movies. Actually cancel your gym membership and hop on a bike (and actually buy a bike because you don’t own one).

- In most towns, you can get by with a $20 rectangular antenna that mounts to a window to get 1080p quality for local networks via OTA TV. In my town, however, my simple antenna didn’t work so I paid $550 for a big-old-antenna to be mounted in my attic. Despite the relatively high upfront cost, from a NPV standpoint it was a complete no-brainer if it allowed me to save >$50/month for decades. We use the antenna all of the time to get free HD OTA sporting events broadcast on the major networks.

- I don’t have much sympathy for people who “have no money to save” despite buying $1k iPhones annually, leasing $70k SUV’s, dining out daily, and vacationing to exotic overseas destinations 2x/year.

- This frugality challenge isn’t metaphorical. If you desire to be wealthier, you must save more today. To do so, you must spend less today. Actually brown bag it to work. Actually call up Verizon/Xfinity to cancel your $200/mo TV/Phone plans. Actually drive a hooptie (my car of choice is a 2010 corolla bought used for $9k with 45k miles on it from mormon missionaries many years ago). Actually use the library in lieu of buying books/movies. Actually cancel your gym membership and hop on a bike (and actually buy a bike because you don’t own one).

- The way to generate these elusive investable dollars is to spend less than you earn. It’s obviously easier to do so while keeping lifestyle inflation in check and trying to grow your earnings.

- FV = PV*(1+R)^N

- The future value (FV) of money is equal to it’s current value (PV) grown by a compounded interest rate (R) over time (N).

- Disciplined DIY index investing, on average, outperforms the vast majority of investing strategies on an after-fee basis.

- Thinking strategically about taxes will make you substantially wealthier than if you ignore it.

- I don’t know if there is a better return on invested time than spending a few hours learning the mechanics of how the US tax code works. I think a few hours of study here can lead to hundreds of thousands of dollars of lifetime tax savings.

- Unless you are Warren Buffet, buying the entire market is more prudent than picking stocks. The vast majority of people aren’t smarter than the market. If you think you are because of your prior successes with stock picking, you’re more likely the beneficiary of prior luck. Congratulations on your past successes, but luck isn’t a very sustainable investing strategy going forward. If you flip a coin enough times, you’ll eventually arrive at an average of 50% heads.

- The US stock market has returned 14%/year for the past 10Y. This is an unbelievable return to the disciplined investor who “only” invested in “boring” low-cost index funds.

- I find the premise that broad market returns are “not enough” is crazy, leading Robinhood-minded investors to monkey around with risky and tax-inefficient individual stock picking.

- Losing your shirt in the market is a part of the normal cycle of investing. As one of my favorite investing authors William Bernstein puts it, “it is the duty of investors to lose money from time to time.”

- With enough experience and practice at losing smaller amounts of money, several hundred thousand dollar investing losses should not elicit panic. It never feels good to watch one’s portfolio go down that much, but it’s a normal part of the process and the prudent response is to stay the course.

- Dollar cost averaging is a more prudent investing strategy than trying to perfectly try to time the market with every single investment contribution. On average (but certainly not always), the sooner you fund your investments, the better off you’ll be.

- Once you your portfolio is sufficiently large, I can’t think of many reasons to incur the opportunity costs of holding emergency funds in cash. Consequently, I’d try to envision any cash you have laying around as slowly burning due to the effects of inflation. I don’t like to have my cash burn, so I try to keep very little of it (almost zero).

- In taxable brokerage accounts, the strategy of buying and holding for life (or as long as possible) is going to be the most tax efficient strategy (and thus produce the highest after-tax returns).

How People Make Mistakes

Despite the simplicity & relative irrefutability of the above statements, I see people making errors on a daily basis:

- Blatant asset allocation errors, such as individuals in their 20’s staying out of equities out of fear.

- Robinhood investing types monkeying around with individual securities and even trading stock options.

- People assert they will “save tomorrow.” But “tomorrow” never comes. Only a bunch of “today’s”.

- Kind of like my vague desires to do a half ironman and eventually write a book!

- A bright & highly educated friend told me he recently put $10k into the market, but pulled it out days later when the market went down. It seems to me that this friend is going to face an uphill battle when trying to grow a retirement portfolio. Losing 1% of a $10k investment indeed creates a painful short-term loss of $100. I’m more interested, however, in the long-term opportunity cost of holding cash. The past decade of 14% returns has generated a $27,072 opportunity cost for those parking $10k of cash on the sideline this past decade (=$10000*1.14^10-$10000). Augment this opportunity cost of cash by another few decades and it’s a fortune. It’s easy to lose sight of this when being slapped in the face by an immediate $100 investment loss in a given day and the incessant flash of tickers on our screens. Volatile stock tickers distract investors from what matters — the magic of compound interest when zooming out over multi-decade horizons.

Hindsight Bias Disclaimer with a Rebuttal

I realize that the post is almost surely reeking of hindsight bias:

- It’s easy to gloat about the success of equities when I’m cherry picking the past decade of 14%/year returns.

- In contrast, historical domestic equity returns have been 10.0%/year from July 1927 to Oct 2020 based on my calculations using Ken French’s data (link).

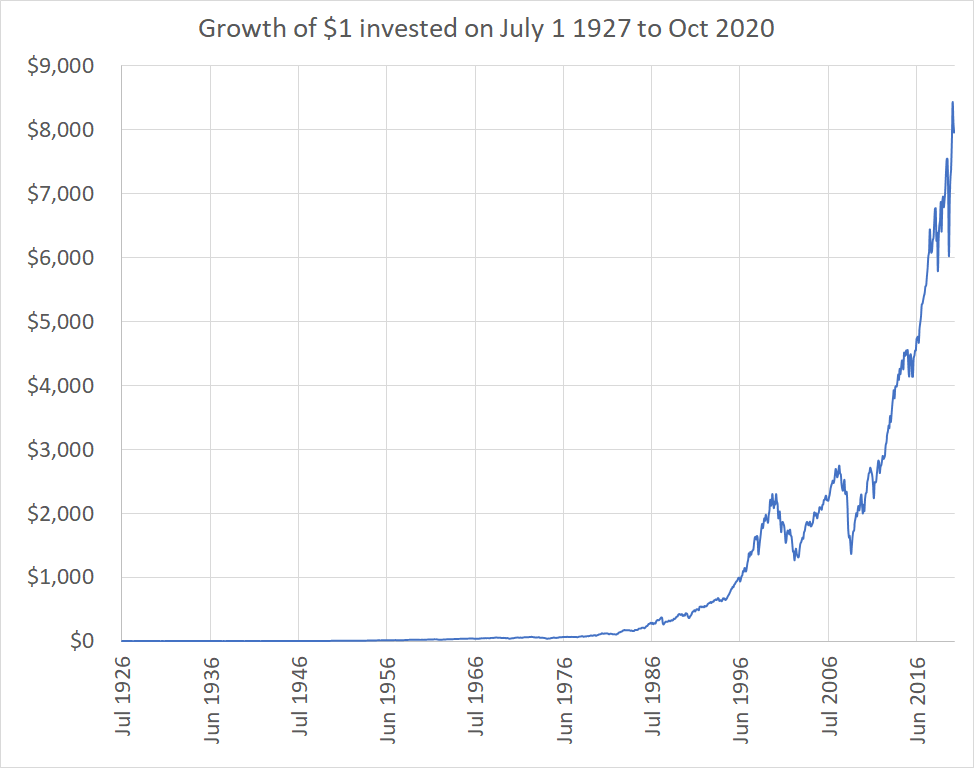

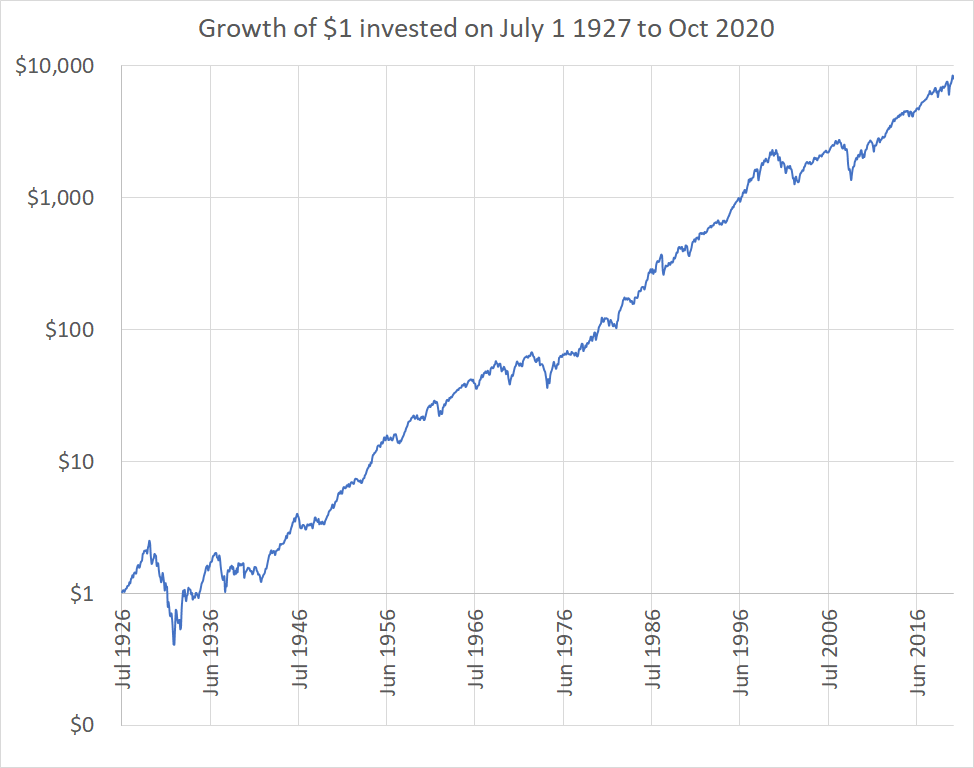

- $1 of invested at the beginning of July 1927 would be worth $7,953.64 at the end of October 2020. This corresponds to a monthly return of 0.797% (=7953.64^(1/1132)-1) or an annualized return of 10.0% (=(1+0.797%)^12-1).

- You can download my edited spreadsheet that contains these calcs & below plots here (link).

- I’m admittedly cherry picking on the historical financial success of the U.S., which is anomalous in the global context.

- In contrast, historical domestic equity returns have been 10.0%/year from July 1927 to Oct 2020 based on my calculations using Ken French’s data (link).

- It’s easy to gloat about the success of equities when I’m conveniently ignoring the underperformance of international stocks, which I also own.

Growth of $1 invested on July 1 1927 to today. Ignores inflation and dividend tax drag.

Growth of $1 invested on July 1 1927 to today. Ignores inflation and dividend tax drag.

Growth of $1 invested on July 1 1927 to today. Ignores inflation and dividend tax drag. Same chart as before but Y axis is now shown in a log scale. To think that $1 invested on my date of birth would be worth about $100 today (ignoring inflation) is crazy. I should probably merge in some inflation statistics but was too lazy to do so. For those feeling more ambitious, you can do so here (link). Looking at this second chart puts an appropriate perspective on “catastrophic” market collapses in my lifetime like the dot com crash of the late 90’s, the financial crisis of 2008, and the recent 30% Covid correction in March of 2020. With a multi-decade investing perspective, these events are all minor minor blips in the grad scheme of things to a buy-and-hold investor who is dollar-cost-averaging through thick and thin.

Investing in 2021 and beyond

Despite the hindsight bias, there are fundamental investing truths that cannot be ignored in today’s environment:

- On an after-tax and after-inflation basis, bonds today are almost surely guaranteeing investors negative returns for the next decade.

- Vanguard’s Total Bond Market Index Fund (link) is currently yielding 1.1%. After paying 30% taxes on that 1.1%, you’re left with an after-tax yield of 0.77%. Subtract inflation and you’re easily negative.

- Equity valuations are sky-high from a historical P/E standpoint

- Domestic P/E: 27.7 (link).

- Here is a chart showing historical trends (link).

- International P/E: 19.1 (link).

- Despite (or maybe because of) the relative underperformance of international stocks recently, from a P/E standpoint they are a more attractive investment right now.

- The dividend yield on equities is higher than the yield of bonds (though there is obviously no guarantee this persists).

- Domestic P/E: 27.7 (link).

- Real estate valuations are also high (link).

- The elevated valuations will necessarily cause future returns to be substantially moderated. Consequently, people must 1.) save more, 2.) focus on reducing fees & taxes.

- An investor disgusted at high valuations right now might rationally bet tempted to sit on the sidelines in cash and wait for a market correction. If one could accomplish this with certainty, it would be a no-brainer. The problem, however, is that the anticipated crash sometimes never comes.

- I’m sympathetic to the argument that a crash could happen tomorrow. I’m also sympathetic to the argument that the current zero interest rate environment is rationally propping up asset prices. Despite the insanity of current asset prices, I’m personally not betting on a market correction because I have an investing philosophy of 1.) not timing the market, and 2.) keeping in mind a (hopefully) 5-decade long investing horizon. When viewing investments over a 5-decade long horizon, I find it easier to stomach market volatility by continuing to dollar cost average and ignoring the noise.

Conclusion

In a text with my MBA buddy yesterday, he shared that he is sitting several hundred grand north of $2M by the age of 40. He’s never owned a home, so he isn’t the beneficiary of real estate wealth created through leverage which seems to be in vogue. I’m almost certain he came from modest means, so he isn’t a trust fund child. He’s just a normal dude who dutifully invested in index funds for two decades.

Since I track my finances in a more detailed manner than anyone I know (it takes 15 min/month), I’m able to readily compute statistics out of thin air (I’m hopeful that others have been inspired to do the same; it’s incredibly enlightening/empowering). Since I started keeping detailed records of our finances in September of 2016, we’ve earned $310,255 in interest from investments, corresponding to an annualized realized return of 13.5%/year. This is sort of nice to know, but I’m much less interested in these numbers than I am at the prospect of another 50 years of compound growth in tax-efficient investment vehicles (and the debilitating consequences of 50 years of inflation on our portfolio).

In a world of stock prices flashing incessantly across computer/TV/smartphone screens and the proliferation of active-trading cultures like Robinhood or reddit.com/r/wallstreetbets/, please don’t lose sight of the forest through the trees. There is much you and I cannot control in the investing world, such as market volatility and inflation. But there is indeed much we can control: 1.) how much we save, 2) our asset allocation, 3.) whether or not to invest in a tax-efficient manner, 4.) whether we invest ourselves or pay 1% AUM fees to someone to do it for you, and 5.) whether to diversify in broad index funds or roll the dice by picking individual stocks.

In order to preserve your sanity (and wealth), I’d encourage you to focus on improving the dimensions of investing that are within your control and ignoring the rest. It’s easier said than done, of course, but will almost certainly help you to be a wealthier, and happier, investor.

As a pension actuary, I can tell you that the professional pension fund managers make many of the same mistakes that individuals do. Primarily, thinking you have to pay for performance when it comes to investments. Related to this, they also do a very poor job of evaluating the effectiveness of their active management strategies. If they did, they would abandon most of them immediately.

Pension plan sponsors also make many of the same mistakes that individuals do. e.g. contributing well under the maximum deductible contribution limit.

Thanks for the insightful comment! What is the “maximum deductible contribution limit” that pension funds face? I was unaware of such a threshold.

One of my WSJ favorite articles in recent memory is from October of 2016, entitled “What Does Nevada’s $35 Billion Fund Manager Do All Day? Nothing”: https://www.wsj.com/articles/what-does-nevadas-35-billion-fund-manager-do-all-day-nothing-1476887420. It is a humorous story of a pension fund manager in Nevada who does nothing but invest in a simple portfolio of index funds, much to the chagrin of his peers. Here’s how the article starts if you don’t have access. The guy is my hero!!!!

Steve Edmundson has no co-workers, rarely takes meetings and often eats leftovers at his desk. With that dynamic workday, the investment chief for the Nevada Public Employees’ Retirement System is out-earning pension funds that have hundreds on staff.

His daily trading strategy: Do as little as possible, usually nothing.

The Nevada system’s stocks and bonds are all in low-cost funds that mimic indexes. Mr. Edmundson may make one change to the portfolio a year.

News doesn’t matter much.

Will the 2016 elections affect his portfolio? “No.”

Oil prices? “No.”

He follows Fed Chairwoman Janet Yellen , but “there’s a difference between watching and acting.”

…..

Ha! That’s a great story.

Employers with U.S. retirement plans can deduct the contributions they make to a qualified defined benefit plan (or defined contribution plan) when determining corporate taxes. The maximum deductible contribution is basically limited at the amount required to fund the plan under very conservative prescribed assumptions.

This isn’t as light-hearted of a read, but Pennsylvania had an independent review of the investment and management of their two largest public pension funds. I consider this to be an actuarial mic drop. I actually found a lot of the analyses and recommendations are applicable for individual investors too.

https://www.psers.pa.gov/About/Investment/Documents/PPMAIRC%202018/2018-PPMAIRC-FINAL.pdf

Thanks for the explanation and for the link! I haven’t read it yet but will do so soon. I’d love to learn more.

Are DB plans still discounting liabilities at 7.5%-8% despite the zero interest environment? If so, that’s asinine! If not, pension plans are going to be facing a severe reckoning as they start implementing more reasonable discount rates.

Josh Rauh at Stanford has done a bunch of finance/econ research about pension funds. Not sure if the actuary world would have heard of him: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=4N9pRgQAAAAJ&hl=en&oi=ao

So, public sector funds typically use their expected return on assets as their discount rate until they project that assets are depleted and switch to a government bond based rate. And, yes, many funds still use unrealistically high rates. Especially considering all of the “volatility reducing” assets they tend to invest in.

Private sector funds are required to base their discount rate on high quality corporate debt regardless of how they’re invested. Their expected return on assets is only used to calculate the upcoming year’s expense. This is for US GAAP. The international accounting standard requires the same high quality corporate debt based rate for discounting and the next year’s expected return.

Can’t say I’ve heard of Josh Rauh, but will check out your link.

Thanks for the clarification! I had no idea that there was such a disparity in the all-important discount rate for public & private pension funds. All else held equal, if public pension funds are discounting liabilities at 7.5-8% while private pension funds are discounting liabilities at corporate bond yields (perhaps 4%? https://investor.vanguard.com/mutual-funds/profile/portfolio/vwehx) — independent of the underlying investment holdings — this means that public pension funds are going to be severely underfunded relative to private pension funds. This is incredible.

Thanks again for enlightening a curious, but grossly uninformed, individual on the crazy world of pension accounting. I still need to dig into that link you sent me.

Professor,

Have you done a research of what happens to portfolio if 10% is invested in physical Gold/ Silver over time? I think someone already did and discovered that 10% improves the returns and reduces volatility.

Also what is your thought to have 1-3% also in Bitcoin/Crypto as diversification?

When you have time can you write your thoughts about it in a blog post?

Please check also this IRA – offers both of them with lowest fees: https://itrustcapital.com

Thank you!

I respect Warren Buffet a lot. Here is what he says about gold in 2011: https://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2011ltr.pdf. I feel similarly to Bitcoin/Crypto as I do gold. The value of gold/Bitcoin/crypto as an investment relies on the existence of a “greater fool” to sell it to some day at a greater price. Perhaps time will demonstrate that I’m the fool for not holding these assets, but I find it hard to ignore Buffet’s logic below. I do, however, acknowledge that there is diversification benefit to holding uncorrelated assets. This diversification benefit, however, has been insufficient to convince me to overlook the pitfalls of these investments.

Over the past 15 years, both Internet stocks and houses have demonstrated the extraordinary excesses that can be created by combining an initially sensible thesis with well-publicized rising prices. In these bubbles, an army of originally skeptical investors succumbed to the “proof” delivered by the market, and the pool of buyers – for a time – expanded sufficiently to keep the bandwagon rolling. But bubbles blown large enough inevitably pop. And then the old proverb is confirmed once again: “What the wise man does in the beginning, the fool does in the end.”

Today the world’s gold stock is about 170,000 metric tons. If all of this gold were melded together, it would form a cube of about 68 feet per side. (Picture it fitting comfortably within a baseball infield.) At $1,750 per ounce – gold’s price as I write this – its value would be $9.6 trillion. Call this cube pile A. Let’s now create a pile B costing an equal amount. For that, we could buy all U.S. cropland (400 million acres with output of about $200 billion annually), plus 16 Exxon Mobils (the world’s most profitable company, one earning more than $40 billion annually). After these purchases, we would have about $1 trillion left over for walking-around money (no sense feeling strapped after this buying binge). Can you imagine an investor with $9.6 trillion selecting pile A over pile B?

Beyond the staggering valuation given the existing stock of gold, current prices make today’s annual production of gold command about $160 billion. Buyers – whether jewelry and industrial users, frightened individuals, or speculators – must continually absorb this additional supply to merely maintain an equilibrium at present prices. A century from now the 400 million acres of farmland will have produced staggering amounts of corn, wheat, cotton, and other crops – and will continue to produce that valuable bounty, whatever the currency may be. Exxon Mobil will probably have delivered trillions of dollars in dividends to its owners and will also hold assets worth many more trillions (and, remember, you get 16 Exxons). The 170,000 tons of gold will be unchanged in size and still incapable of producing anything. You can fondle the cube, but it will not respond. Admittedly, when people a century from now are fearful, it’s likely many will still rush to gold. I’m confident, however, that the $9.6 trillion current valuation of pile A will compound over the century at a rate far inferior to that achieved by pile B.

Consequently, I personally choose to ignore investing fads and keep it simple with broad-based tax-efficient equity index funds. Eventually I’ll add bonds to the mix, but with negative real yields I’m not tempted to switch quite yet.

Also with the Crypto you can make up to 8.6% interest with the stable coins form here:

https://blockfi.com/crypto-interest-account

Maybe I’m old school, but earning 8.6% interest when the prevailing interest rate is 0% doesn’t seem right to me. How do you explain the underlying economics of how this works in a zero interest rate environment?

This is how the underlying economics of interest account works: https://blockfi.com/earn-bitcoin#:~:text=BlockFi%20Interest%20Account%20clients%20can,earn%20bitcoin%20while%20they%20HODL.

Their response isn’t computing in my head, so I’m personally steering clear of it. Good luck with your crypto investments!

Warren Buffett buys gold in 2020: https://www.kitco.com/news/2020-08-14/Warren-Buffett-buys-gold.html

Well I’ll be damned! I hadn’t heard of his change in heart! He so adamantly rejected it as a viable investment for years, this comes as a shock to me.

Thanks for sharing!

I think it’s worth pointing out he bought Barrick Gold Corp, a mining business, not gold bullion. My view is he isn’t being inconsistent and, rather, is making a bet on an undervalued company that was trading less than recent historical earnings. Just because he thinks gold is a chunk of metal that produces no real value, doesn’t mean he thinks that the business won’t be successful.

I didn’t catch that when skimming the headline. Thanks for the clarification!

Buffett subsequently sold off more than 40% of his August purchase of Barrick Gold stock. When news of his selloff became public the stock price tanked.

https://www.fool.com/investing/2020/12/07/why-shares-of-barrick-gold-plunged-13-in-november/

Aside from whatever is in my wedding ring and a gold chain given to me by my godfather as a college graduation present, I am content to have my only holdings of gold mining stocks those located within broad indices. (I assume there is some Barrick GOLD within VXUS, for example.)

Thanks for the update on the Barrick story!

While Buffett is surely without flaws (e.g. famously failing to see the rise of tech and passing early and regularly on tech investments like Google), I sure admire his disciplined approach to investing (paraphrasing): “if I don’t understand it, I don’t invest in it.” Following this mantra has certainly saved my bacon through the years as I’ve avoided countless investing fads.

Like you, I’m perfectly content to only hold gold indirectly through broad based indices.

I like the metaphor of individual investors being pension fund managers. In my mind, a big part of the problem with the current 401(k)/etc. system is that it creates a henhouse guarded by foxes (the financial industry). I look forward to seeing programs like CalSavers and OregonSaves, state run, IRA-based pension funds that don’t have the same conflict of interest that the financial industry has. A quick glance at their target date funds shows generally lower fees (e.g. net ER of .09% for their TDF 2045, compared to .15% on Vanguards 2045 TDF). I like the idea of everyday folks being able to buy into a “pension” of sorts.

As far as crypto goes, if you don’t understand it, you shouldn’t be investing in it. I understand it and there’s no way I’d put money into it. It’s all castles in the air.

I like your analogy of the henhouse being guarded by the foxes. That indeed is how the system is operating. I can’t say that I know much about CalSavers and OregonSaves, but your comment has inspired me to look more into it.

I’m glad I’m not the only crypto skeptic here. Perhaps time will demonstrate that both of us are fools as Bitcoin ascends to the world’s only universal currency, but I think there is way too much downside risk to bother with it. It reeks of a Ponzi scheme to me.

Hi Prof, I have been reading your blog for about 1 year, really really helpful and inspired me for personal finance planning!

BTW, can you please share the model of attic antenna you’re using? I’m thinking to upgrade my small Mohu indoor antenna.

Thank you!

Here’s a pic of an antenna similar to mine: https://www.dropbox.com/s/ex919abw7b4hmcc/antenna%20example.jpg?dl=1

In grad school in a bigger city, this one worked great for us: https://amzn.to/2KCtMfc

I just googled “antenna installation my_city, my_state” and found a dish satellite installer who was also doing these installations on the side. It wasn’t cheap, but I think it was well worth it for decades of free TV.

Not sure if I’ll have to update when OTA converts to 4k in the future.

I think Sling TV the streaming service installs antennas for around 100$. Another decent alternative if it is available in your city is locast.org It essentially gets you local channels for 5$ a month.

Thanks for the suggestions! Nice to know there are other OTA weirdos out there!

Thanks for sharing your thoughts. Sometimes, I feel like we should thank the people who are upgrading to a new thing every year! It appears to me that this country’s economy is strong because people spend the money. In my home country, people used to be thrift savers and they save money not only for them but also for the generations to come. But now this is changing in my home country too because companies are quite successful in convincing people to spend money. It seems like marketing + free (i.e. pay indirectly) hard to resist.

I agree that consumerism drives the economy, and thus stock returns, and thus my personal wealth. I’m financially benefiting at other people’s financial expense and the expense of the world as its resources are depleted at an alarming rate (not to mention pollution, etc).

On the one hand, I’m thankful for consumerism. On the other hand, I hate it.

On the anti-consumerism dimension, this guy is my hero: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKirXBZV7hE4Fws3VSdYkRQ

Really enjoy your blog and think it is a valuable resource.

What percentage of your age group do you think is saving (or will save) enough to live on in retirement?

Assuming that percentage is quite low, what happens when very few have enough to live on in retirement? Massive government intervention?

I get the sense that most people are in trouble for retirement, but I can’t quantify it very scientifically off the top of my head.

What will people do without money? Live off of social security. If that is insufficient, they’ll rely on the sympathy of family members. In the absence of family members, they’ll rely on social safety nets such as food stamps and medicaid. When social security benefits are inevitably cut, it will become harder for this subset of individuals.

Yeah, but with a massive % of people not saving properly for retirement, I have the feeling that the government is likely to bail these folks out in some way. Guess it probably isn’t wise to speculate about that….and as our mutual friend Joey has said, living frugally actually has a lot of benefits, even if it somehow does not pay off in the end.

I’m really not sure what the end game is for such a pervasive problem. Looking at the experience of family members living solely on social security, it’s not something I’m particularly eager to do and looks wrought with risk (e.g. one leaky roof, car repair, or faulty A/C away from financial catastrophe).

It seems that our government is increasingly willing to bail people out rather than let people face the consequences of their actions (e.g. medicaid expansion, democrat’s recent discussions of wiping away $50k per student in student loans, etc). I’m certainly sympathetic towards those who, though no fault of their own, are struggling to survive. The challenge is to protect such individuals while not incentivizing poor behavior. Had I known that $50k/student in forgiveness was coming, I would have taken out $50k in student loans during my phd/mba/undergrad to take advantage of the free money. I just get frustrated when the rules of the change in the middle of the game. This recent NBER paper describes how such a policy is regressive (disproportionately helping the rich), which seems an odd policy decision: https://www.nber.org/papers/w28175

We study the distributional consequences of student debt forgiveness in present value terms, accounting for differences in repayment behavior across the earnings distribution. Full or partial forgiveness is regressive because high earners took larger loans, but also because, for low earners, balances greatly overstate present values. Consequently, forgiveness would benefit the top decile as much as the bottom three deciles combined. Blacks and Hispanics would also benefit substantially less than balances suggest. Enrolling households who would benefit from income-driven repayment is the least expensive and most progressive policy we consider.

“I don’t have much sympathy for people who “have no money to save” despite buying $1k iPhones annually, leasing $70k SUV’s, dining out daily, and vacationing to exotic overseas destinations 2x/year.”

Agree with this and many other points in the post. This may vary by state but around here 75% of all commercial airtime on TV is car advertisements. I have not owned a car in 10 years. TEN. The average cost of a car is about $38,000. I’ve spent about $2,000 on transportation, total, over 10 years. There isn’t any public transit, and I don’t live in a big city where everything is walking distance. But I used my brain to figure it out. I don’t see myself as incredibly frugal; however, one thing that blows my mind is why people pay so much for transportation but are nonchalant about more longstanding topics.

I generally agree that TV is crap. However, a DVR (we used to use Window’s Media Center which was awesome; we now use Plex) makes it tolerable since we can skip commercials. Shark Tank and American Ninja Warrior are family favorites. My wife and I love This is Us.

Some of my best memories as a kid were watching football with my father. My boys love to watch football, so I allow it. I think it’s been a fun tradition.

Congrats on the $200/year transportation expenditure. That’s incredible. Transportation is a huge line item on most people’s budgets, so “using your brain” (as you say) to help minimize this cost will pay huge dividends (literal and figurative) for decades in the future.

The $20 rectangular antenna by the window can be used for both TV and FM radio with a splitter. I didn’t even bother to mount it. Just sitting loose behind the blinds worked for me.

As always, TFP drops the knowledge-bomb! I ahd no idea that the antenna could also be used as an FM splitter. Neat trick. Thanks for sharing!

Do you have any OTA TV antenna hacks? E.g., do you use it in conjunction with any DVR software? I used to use Windows Media Center prior to its deletion on Windows 10. It was fantastic. Plex is okay, but not nearly as robust of a DVR as WMC was.

Setting the OTA antenna on top of three stacked locker shelves (e.g., https://www.bedbathandbeyond.com/store/product/honey-can-do-reg-stackable-steel-folding-locker-shelf-in-black/1045753282?skuId=45753282) seems to help…. 🙂

Brilliant! In hindsight, perhaps I could have saved myself the $550 antenna installation expense….

Hi,

You mentioned that you strive to keep near percent cash allocation due to opportunity costs of not investing in the market.

In that instance, how do you think about and address significant emergency expenses ? Do you just liquidate your equity to cover it even if market happens to be undergoing a correction at that moment? Or is the liquid cash while small, still sufficient to cover emergency fund uses ?

Good question.

If I needed to cover a $10k expense and couldn’t cash flow it, I’d sell some equities. Credit cards give ~45 days of interest free float so that would help too. If this liquidity event coincided with a market correction, then I’d unfortunately end up selling at a “low”.

So, I guess the economic tradeoff is opportunity cost of holding excess cash (e.g. 14%/year for the past 10 years) vs the probability of an emergency * the probability of selling at during a market correction * the “cost” of selling during a market correction. Admittedly, for a prolonged job loss spurred by a recession (i.e. Covid), the correlation between “emergency” and “selling low” is greater than zero. If the correlation between these events were zero (e.g. if someone had a really secure job), I think you can make the case that emergency funds make even less sense.

Generally, I prefer having piles of investments (mostly liquid in the case of a taxable brokerage account + Roth IRA + HSA) as protection. I think it’s more prudent than the alternative: $10k of cash + fewer assets.